Updating A Sweet History

How Bissinger’s and Chocolate Chocolate Chocolate Are Scaling a Legacy — All the Way to Nashville, New York and Florida

by Craig Kaminer / photos by John Lore

Walk into Bissinger’s Handcrafted Chocolatier and sister company Chocolate Chocolate Chocolate Company’s candy kitchen on The Hill in St. Louis and you’ll hear the rhythms of a factory that has never lost the human touch: Copper kettles hissing softly, caramel cooling in measured sheets, a chocolatier’s gloved hand guiding a ribbon of tempered couverture into perfect shine. For decades, Bissinger’s — one of the oldest names in American confectionery — and the Abel family’s Chocolate Chocolate Chocolate Company have been guardians of that craft. Today, they’re doing something harder: translating hand-made heritage into modern growth, with a bold expansion plan that plants the St. Louis chocolate story in two of America’s most competitive arenas — Nashville and New York City.

Dan Abel Jr., Bissingers Chief Chocolate Officer

“My parents started a candy company and, literally, I grew up on the production floor in a candy kitchen, so my brother, sister and I have been working in the business in some fashion since I was 10 years old,” Dan Abel Jr., Chief Chocolate Officer, says. “The dinner table was the family business. Summers on the line, holidays in shipping, retail weekends, unloading trucks, loading trucks — We all wanted to get involved in the business as we came out of school.”

If growth looks inevitable from the outside, it didn’t feel that way inside. “Did we expect it to be at this size at this time?” he asked. “No… it was the pipe dream of a what-if? Every day’s been fun — some stressful — but you forget about the stressful days and wake up the next morning like, ‘I just want to do it again.’”

That bias toward the work — learn every station, know every constraint — defined Chocolate Chocolate Chocolate’s culture long before the Bissinger’s acquisition. “There was never a budget to do anything,” Abel says. “We had to find a way to make something happen… [It was] a very tight-run organization.” Today it’s called bootstrapping. “I created the trade show booth. I drove it up. I merchandised it. I worked the boot. I wrote the orders and then I came home and fulfilled them.”

Over the last 15 years, the premium chocolate landscape has consolidated. “From when we first met to today, you wouldn’t even recognize it,” Abel adds. “If I identified 20 manufacturers I knew in 2010, there’s two or three left. Everyone else has been swallowed up by private equity or closed or merged. Where private equity money did take hold, he observed a narrowing: “If they made 50 items, they identified their best five and scaled those… changing the distribution model.”

The Abels zagged. “We went to handmade chocolates… handcrafted truffles in bulk and then packaged in gift boxes and seasonal. That’s the business that built everything.”. Attempts to automate — decorators, caramel extruders — were sold off. “Every time we get into a pinch point where we can’t produce enough, instead of buying a big line, we buy another small line for a team of three. Now we have nine.”

It’s also why Bissinger’s made perfect sense.

“When Bissinger’s was for sale they were a handmade operation; we’re a handmade operation,” Abel says “Obviously, the brand is phenomenal — chocolatier to the king in the 1600s — and we needed to replace a seven-figure customer that had gone bankrupt.” The deal, he admits, was “the most complicated acquisition” he’s done, but the fit was unmistakable.

Consumers felt it, too. “When a competitor buys a beloved local brand, the reaction is often fear: they’ll close it, change it,” Abel says. “What most people didn’t know was how many core Bissinger’s team members had already come over to Chocolate Chocolate Chocolate over the years. We were more like the old Bissinger’s than the new Bissinger’s was.” The mandate post-acquisition: Stay hyper-focused on handcraft and keep elevating packaging.

At first glance, a heritage catalog program might sound quaint in a world of targeted ads and one-hour delivery. Abel counters with data and devotion. “Bissinger’s still prints, designs and produces seven national catalogs a year. Almost everyone’s getting out of catalogs, but our catalog business continues to grow,” he says. When the Abels took over in mid-2019, they quickly asked, ‘‘When’s the Thanksgiving catalog art going to be done?” I said, “I have no idea how to make a catalog, but let’s figure it out together.” They did — pulling from archives, rehiring a photographer, learning on the fly.

The result isn’t a retro indulgence; it’s a conversion engine. “In 2019, we were about 60/40 online to phone. Now it’s 90 percent online, but we’ve tripled the online business.” The phones still ring. “Ten percent of a bigger company is roughly equivalent to the old 40 percent,” he notes, but the catalog drives digital discovery.

COVID forced more pivots. “We focused almost 100 percent on direct-to-consumer” Abel says, while wholesale buyers triaged essentials. Post-pandemic, independent specialty boutiques came roaring back, hungry for distinctive confections. Now, the pendulum is swinging to luxury retail — which sets the stage for Nashville and New York.

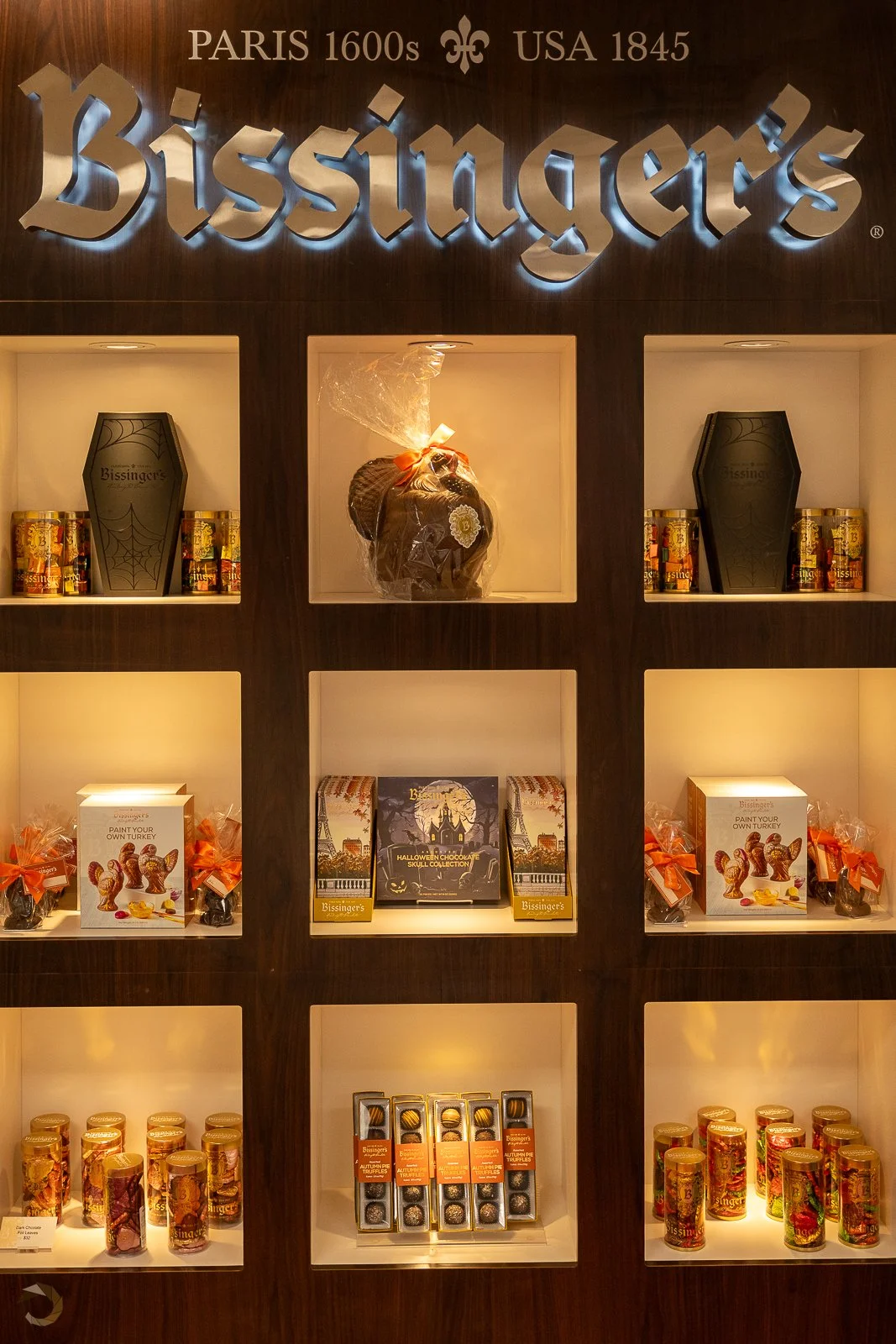

Nashville’s The Mall at Green Hills puts Bissinger’s in front of an affluent, fashion-attentive audience; New York’s Macy’s Herald Square places the brand inside American retail mythology. Both shops are built around four levers: assortment architecture (approachable indulgences up to prestige “hero” boxes), customization (seasonal sleeves and local motifs), live craft moments (guided tastings, hand-finishing demos) and a corporate gifting desk for concierge-level service.

The hospitality piece starts at home. “We opened a café for tourists here for factory tours,” Abel says. “You can stop by the coffee shop, get lunch. We’ll add wine and beer next, then birthday parties, events, a speakeasy bar.” The goal: Turn a 30-minute walk-through into a 90-minute destination. Demand is already there. “We’re at 55,000 tours a year,” he says. “We turn people away and we’re always selling out.” With the expansion, “we can double that [to] bring 100,000 people a year without stressing the facility.”

What surprises visitors most? “The number of steps it takes to make a product: caramel cooked in small copper kettles, poured onto tables, cut into perfect squares, lines running very slowly because handcrafted chocolates run slowly,” he says. “Salted caramels sprinkled or striped by hand — hands with gloves, of course.” He jokes about pop-culture expectations. “There should be some machine spinning — like Lucille Ball—but almost every other facility is going that way. We want to go in the opposite direction.” (They even filmed a playful “speed it up” spoof with Barnes & Noble’s social media team.)

Ironically, the catalyst for the coast-to-coast push started at 3:00 a.m. in a St. Louis warehouse the week before Christmas. “My siblings, our head candy maker and I go help pull online orders from 3 a.m. to 5 p.m.,” Abel says. “In the blur of labels, one pattern glowed: Florida. It wasn’t 1/50th of the orders; it was like 20 percent.” Missouri and Illinois led shipments, Florida was next. Palm Beach became the first out-of-market boutique — and a master class in approvals. “We sent samples, a brand deck, had meetings a six-month process,” he says. Eventually, they got the green light.

Then the wheel began to spin faster. A real estate broker introduced new sites; parents scouted, off-market gems appeared. “We were at zero. Then we were at three.” He laughs at my raised eyebrow. Three? “We’re doing seven: five in Florida and New York and Nashville,” he says, adding they’re “reviewing 10 more.” The measured plan is to commit to 10, then pause to tune the infrastructure. “We’ve been hiring key leadership — recruiting, HR, a director overseeing them — so we find the right people to continue it.”

The moment still rattles him. “When we signed Palm Beach, everything went quiet for a second. I was actually stunned and I can never stun myself. And then New York kind of did that to me too.”

New York happened in the seams between a presentation and a phone that actually rings. A new director of sales pushed for a Bissinger’s “gold box” presentation to Macy’s. Abel decided to pitch the future — premium boutiques in premium markets — anchored by Palm Beach renderings. Mid-call, the lead buyer paused. “You’re opening in Palm Beach?” Yes. “Why don’t you take our New York store?”

Cue another pause. “Excuse me. You have a store in New York?” Sixth floor, Herald Square. Abel told his team, “If the leasing director calls tomorrow, we’ve got something.” By 8 a.m., the call came — with a catch: open by November or it’s 2026. He said yes. “You can’t say no to these things.”

Nashville? A similar mix of persistence and serendipity. “I really wanted to be there. They said there’s nothing available.” A map review later, a larger space appeared — double the size — if Bissinger’s could open by Christmas. “Too good a location to sit empty,” the leasing director warned. Another family summit; another leap.

The romantic part of chocolate is flavor and shine; the unromantic part is everything else.

“Right now, we’re in a chocolate crisis. We’re paying north of $1 million a year more than last year,” Abel says. “We’re floating minimal increases over a couple of years, so we don’t shock the system.” It’s not the first time. Vanilla went from $100 to $350 a gallon in 2019. “Competitors downgraded quality,” Abel says. “Absolutely not for us.

“The reason people get lucky, in my opinion, is when you make the product as perfectly as you can every single time,” he says. That readiness also won them contract manufacturing for some major brands. “Instead of cashing in and taking a trip to Hawaii,” they bought state-of-the-art Swiss molding lines and automatic wrappers, a distribution center down the street, a new ERP — compound investments that, by 2018, had them sitting on 55,000 square feet and the capacity to say yes when Bissinger’s surfaced. “Two thousand and nineteen wasn’t why it worked. The previous five years of disciplined, great things were why it worked,” he says. “I still pinch myself.”

Bissinger’s has always been a people story — on both sides of the counter. My earliest memories of visiting St. Louis from New York included molasses lollipops stuffed into my bag by my future in-laws. “There was always a Bissinger’s moment” I tell Abel in the factory. He nods. The team still thrills when that moment goes viral. “Andy Cohen posted about our chocolate gooey butter cake with Companion,” he recalls. “I was in the warehouse; suddenly online traffic is going crazy.” Celebrities buy — they keep their names quiet — but the real engine is the family that returns every holiday, the neighbor who brings a gold box to dinner, the new Nashvillian who makes a 12-piece assortment their weekly ritual.

It’s easy to romanticize chocolate. Bissinger’s history invites it. But growth is in lease negotiations and HVAC, cool-chain and casework, staffing models and margin math. What makes this St. Louis story different is how each unromantic decision bends back to a romantic ideal: Keep the craft visible, slow where it must be slow, generous where it must be generous.

“If we had a time machine back to 2008, I don’t think I could do it again,” Abel confesses with a grin. “We had so many amazing opportunities fall into place and we seized the moment. We found the right people, were in the right place at the right time.” Then the part that isn’t luck: “Always make a phenomenal product. Never sacrifice. If chocolate doubles in price, it doubles. We deal with it.”

We step onto the factory ramp for a last photo. Somewhere between the copper kettles and a signed lease in Herald Square, St. Louis figured out how to scale what can’t be faked. If you’re near Nashville this season, watch a ribbon get tied, hear the whisper of embossed tissue. If you’re on 34th Street, ride the escalator to six and let a truffle catch the light. The technique is centuries old; the energy is right now.