The Midas Touch

A secret resource not all designers share, Jim Slattery of Gilders Tip is a genius at creating artful furniture.

by Alexa Beattie / photos by Kate Munsch

Decorative artist Jim Slattery goes to some old drawer in a corner of his studio and pulls out a small 3-inch-square packet. Inside, between slips of apricot-colored tissue — and catching on a bar of early autumn sunlight — are leaves of 23 carat gold (95 percent pure).

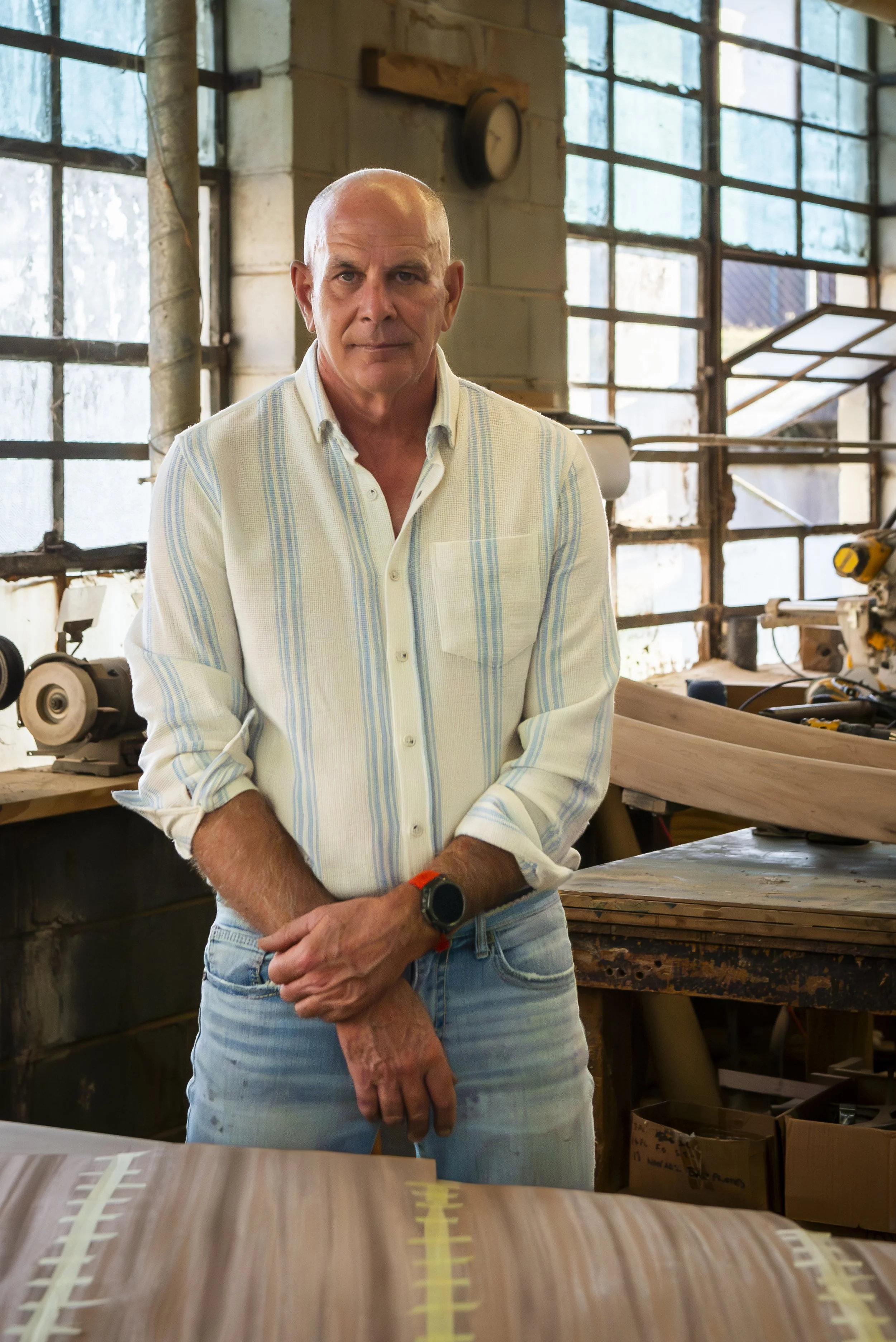

Jim Slattery of Gilders Tip.

“Look,” he says. “One-hundred-thousandth of an inch thick.” He picks at a leaf — thin as the finest membrane — which disintegrates on his fingers. “I love this so much. There’s just something about it.” It is the goldest thing you ever saw. Although Slattery has had his own restoration, furniture design and fabrication business — called Gilders Tip –— for almost 40 years, he was not much more than a boy when his great uncle — a master gilder and sign writer — taught him the art of gold leafing. It can be a 20 or so step process, Slattery says, which mostly consists of prep work for inlaying that impossibly gossamer, impossibly beautiful precious metal into frames, signage, tabletops and liturgical furnishings.

You find Slattery around the back of a tattoo shop on Hampton Avenue. You know you’ve arrived somewhere rather interesting: The garage doors are open, the fans are going full pelt and, in the distance, behind some fine pieces of mid-century furniture and a huge dusty-blue sanding machine, Cathy Roth is working on the veneer for a commissioned mahogany dining table. She explains that she is working in sections: the table will measure 5-feet by 10-feet — too big for the veneer press. It will be oval in shape and purchased by an undisclosed buyer for around $17,000.

Roth is a graduate of the Art Institute of Chicago and has worked with Slattery for almost 20 years. The pair may be the only artisans in St. Louis dealing in the five “noble” materials of the Art Deco era which produced much of the furniture Slattery happens to like best. Those materials are shagreen (which is the term for various kinds of hide; primarily stingray, dogfish and certain types of shark), leather parchment, gypsum (a cloudy, glass-like mineral), straw (which Slattery sources from a farm outside Paris Missouri or France?) and eggshells which he gets from Schnucks.

“When I’m working with those, I’m eating a lot of eggs,” he says. Depending on size, a project may require the shells from hundreds of eggs and is a lengthy process of bleaching, painstakingly removing membranes and gently cracking the shells into tiny mosaics.

“Jim Slattery is an absolute magician,” said St. Louis interior designer Dana Romeis. “He can repair and build. He can duplicate. He can turn metal hinges and hardware. Do you want eggshell or straw marquetry? Do you want white gold or yellow gold?”

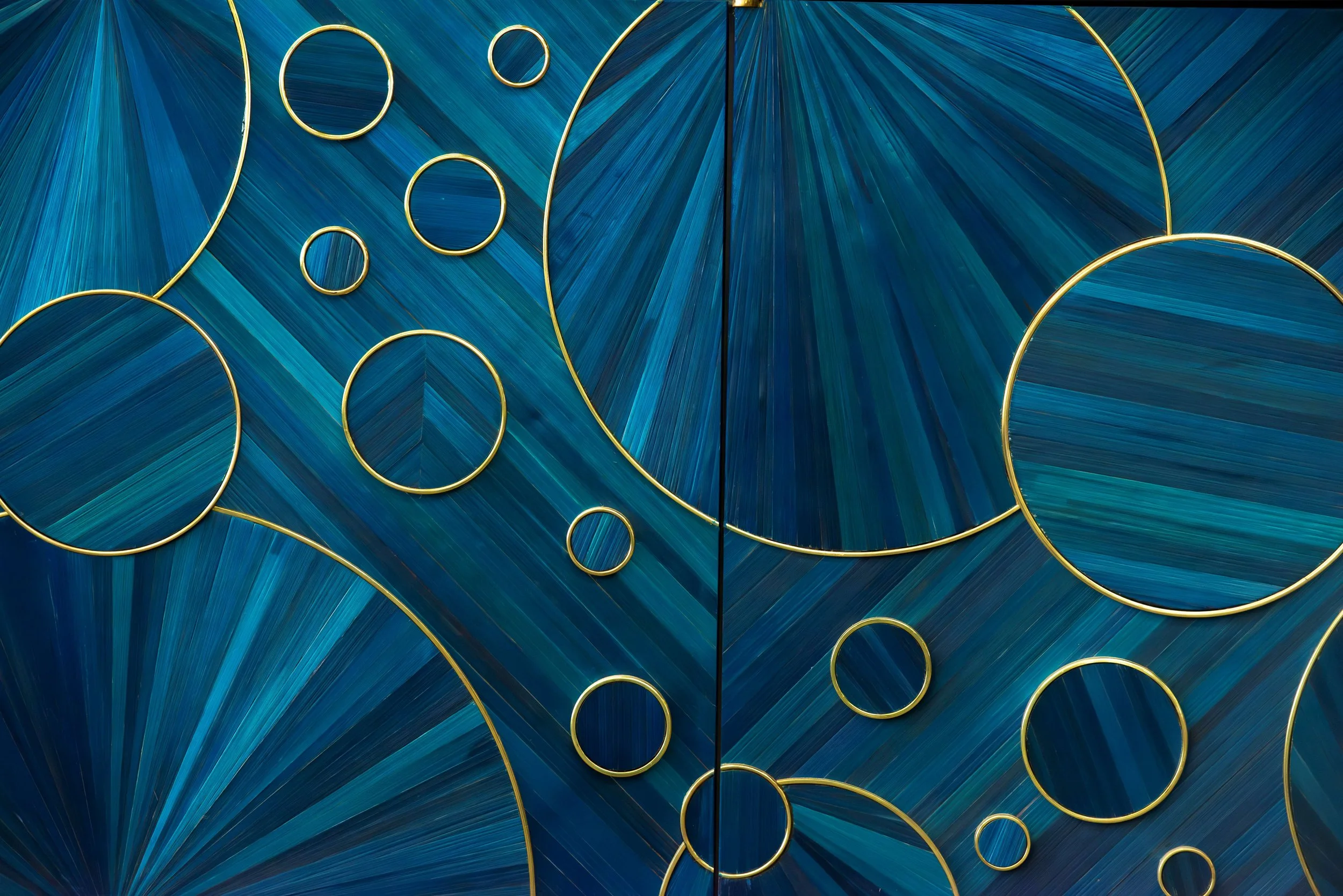

Slattery points out (though it’s pretty hard to miss) a “bubbled” peacock blue buffet. “I call it my Lawrence Welk cabinet,” he says, referring to the bubbly effects at the end of “The Lawrence Welk [TV] Show”, which he watched as a boy with his grandparents. Mid-century in style, the cabinet is a stunning example of marquetry, which is the art of applying pieces of veneer to a structure. In this particular instance, the veneer is blades of rye grass — dyed, steamed flat and ironed into ribbons which Slattery then meticulously laid within and around the decorative brass rings in various sizes. It took him months.

He goes off to another drawer, comes back and slaps down a small flap of shagreen with tail and eye holes: stingray hide, a biproduct of the Philippines fishing industry. It’s the loveliest shade of cream, minutely patterned. Historically, stingray was used in bookbinding, but Slattery plans to ornament a tabletop. At around $200 for a small piece, it is not the cheapest of materials, he said.

Meanwhile, Cathy works on her own marquetry. She pulls out a little side table, similarly applied with straw, but in this case, dyed to various sublime shades of sea green. The table has delicate legs made of spalted maple, which means the wood is finely and intriguingly veined by a dark fungus. The fungus, Slattery said, is encouraged by burying the wood in the ground for a year. A local company — Lumber Logs in North City — is his supplier.

He gives a little tour of his space where he’s now been for 36 years: the sanding machine and its laundry line of spare belts, the spray room like a padded cell (which oddly smells of grapes), the pots and pots of varnish, the tangle of tubes and spray guns. And then the pieces of furniture waiting in the wings to be brought back to life. (Cinderellas waiting on their fairy godfather?). Slattery points out a 1920s bench that originally came from a Chicago courthouse. It’s a sad old thing, cracked and lusterless. You want to tell it it’s in good hands, but it’ll know soon enough. It’s up next after his current, somewhat outré project, which is to refinish a 17-foot maple “booze slide” (not his words) belonging to a St. Louis club. “It was getting worn out; people were snagging their clothes,” Slattery said.

And then there are the pieces he designs and builds from scratch: the insanely handsome “mid-mod” fluted credenza made of snowy cast resin and walnut which will be listed online for around $10,000 and a similarly mid-century games table of cloud-patterned burled laurel. The table happens not to be from his own blueprint, he explained, but has New York's Parsons School of Design to thank for its origination.

“I really like the Paris style of Art Deco; anything from the 20th century,” he says. “I studied the artists from that period and love their designs.”

“There is no one else in St. Louis who does what he does.” Romeis said. “Every client I’ve sent to him loves him and treasures his pieces. He should be selling things in New York for twice the price.”

Slattery is a St. Louis boy. He grew up in the county and went to Pattonville High School. College was not for him, he said. And, clearly, it did not need to be.